What are incoterms

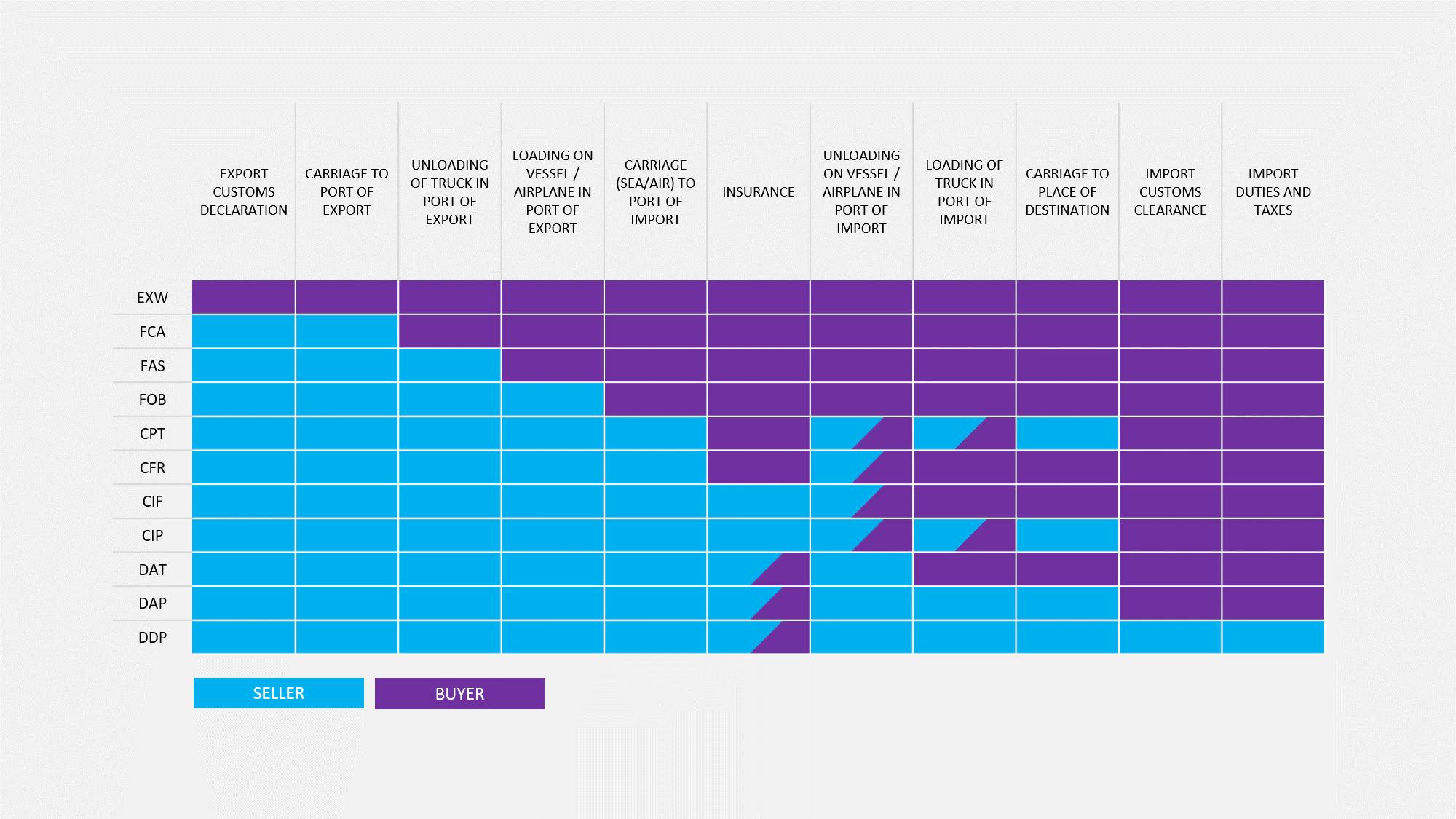

Knowledge on Incoterms is crucial to negociate a correct rate with the carriers and know where your risks are!

Incoterms 2010

(from WIKIpedia)

National Incoterms chambers

Incoterms 2010 is the eighth set of pre-defined international contract terms published by the International Chamber of Commerce, with the first set having been published in 1936. Incoterms 2010 defines 11 rules, down from the 13 rules defined by Incoterms 2000.[5] Four rules of the 2000 version ("Delivered at Frontier"; DAF, "Delivered Ex Ship"; DES, "Delivered Ex Quay"; DEQ, "Delivered Duty Unpaid"; DDU)[6] were removed, and are replaced by two new rules ("Delivered at Terminal"; DAT, "Delivered at Place"; DAP) in the 2010 rules.

In the prior version, the rules were divided into four categories, but the 11 pre-defined terms of Incoterms 2010 are subdivided into two categories based only on method of delivery. The larger group of seven rules may be used regardless of the method of transport, with the smaller group of four being applicable only to sales that solely involve transportation by water where the condition of the goods can be verified at the point of loading on board ship. They are therefore not to be used for containerized freight, other combined transport methods, or for transport by road, air or rail.

Incoterms 2010 also formally defined delivery. Before, the term has been defined informally but it is now defined as the point in the transaction where "the risk of loss or damage [to the goods] passes from the seller to the buyer."[7]

Incoterms in government regulations

In some jurisdictions, the duty costs of the goods may be calculated against a specific Incoterm: for example in India, duty is calculated against the CIF value of the goods,[8] and in South Africa the duty is calculated against the FOB value of the goods.[9] Because of this it is common for contracts for exports to these countries to use these Incoterms, even when they are not suitable for the chosen mode of transport. If this is the case then great care must be exercised to ensure that the points at which costs and risks pass are clarified with the customer.

Defined terms in Incoterms

There are certain terms that have special meaning within Incoterms, and some of the more important ones are defined below:[10]

Delivery: The point in the transaction where the risk of loss or damage to the goods is transferred from the seller to the buyer

Arrival: The point named in the Incoterm to which carriage has been paid

Free: Seller has an obligation to deliver the goods to a named place for transfer to a carrier

Carrier: Any person who, in a contract of carriage, undertakes to perform or to procure the performance of transport by rail, road, air, sea, inland waterway or by a combination of such modes

Freight forwarder: A firm that makes or assists in the making of shipping arrangements;

Terminal: Any place, whether covered or not, such as a dock, warehouse, container yard or road, rail or air cargo terminal

To clear for export: To file Shipper’s Export Declaration and get export permit

Variation of Incoterms

Parties adopting Incoterms should be wary about their intention and variations. The desire of the parties should be expressed clearly and casual adoption should be refrained. Also, making additions or variations to the meaning of a certain term should be carefully done as parties' failure to use any trade term at all can produce unexpected results.[1]

Rules for any mode of transport

EXW – Ex Works (named place of delivery)

The seller makes the goods available at their premises, or at another named place. This term places the maximum obligation on the buyer and minimum obligations on the seller. The Ex Works term is often used while making an initial quotation for the sale of goods without any costs included.

EXW means that a buyer incurs the risks for bringing the goods to their final destination. Either the seller does not load the goods on collecting vehicles and does not clear them for export, or if the seller does load the goods, he does so at buyer's risk and cost. If the parties agree that the seller should be responsible for the loading of the goods on departure and to bear the risk and all costs of such loading, this must be made clear by adding explicit wording to this effect in the contract of sale.

There is no obligation for the seller to make a contract of carriage, but there is also no obligation for the buyer to arrange one either - the buyer may sell the goods on to their own customer for collection from the original seller's warehouse. However, in common practice the buyer arranges the collection of the freight from the designated location, and is responsible for clearing the goods through Customs. The buyer is also responsible for completing all the export documentation, although the seller does have an obligation to obtain information and documents at the buyer's request and cost.

These documentary requirements may result in two principal issues. Firstly, the stipulation for the buyer to complete the export declaration can be an issue in certain jurisdictions (not least the European Union) where the customs regulations require the declarant to be either an individual or corporation resident within the jurisdiction. If the buyer is based outside of the customs jurisdiction they will be unable to clear the goods for export, meaning that the goods may be declared in the name of the seller by the buyer, even though the export formalities are the buyer's responsibility under the EXW term.[11]

Secondly, most jurisdictions require companies to provide proof of export for tax purposes. In an EXW shipment, the buyer is under no obligation to provide such proof to the seller, or indeed to even export the goods. In a customs jurisdiction such as the European Union, this would leave the seller liable to a sales tax bill as if the goods were sold to a domestic customer. It is therefore of utmost importance that these matters are discussed with the buyer before the contract is agreed. It may well be that another Incoterm, such as FCA seller's premises, may be more suitable, since this puts the onus for declaring the goods for export onto the seller, which provides for more control over the export process.[12]

FCA – Free Carrier (named place of delivery)

The seller delivers the goods, cleared for export, at a named place (possibly including the seller's own premises). The goods can be delivered to a carrier nominated by the buyer, or to another party nominated by the buyer.

In many respects this Incoterm has replaced FOB in modern usage, although the critical point at which the risk passes moves from loading aboard the vessel to the named place. It should also be noted that the chosen place of delivery affects the obligations of loading and unloading the goods at that place.

If delivery occurs at the seller's premises, or at any other location that is under the seller's control, the seller is responsible for loading the goods on to the buyer's carrier. However, if delivery occurs at any other place, the seller is deemed to have delivered the goods once their transport has arrived at the named place; the buyer is responsible for both unloading the goods and loading them onto their own carrier.

CPT – Carriage Paid To (named place of destination)

CPT replaces the C&F (cost and freight) and CFR terms for all shipping modes outside of non-containerized seafreight.

The seller pays for the carriage of the goods up to the named place of destination. However, the goods are considered to be delivered when the goods have been handed over to the first or main carrier, so that the risk transfers to buyer upon handing goods over to that carrier at the place of shipment in the country of Export.

The seller is responsible for origin costs including export clearance and freight costs for carriage to the named place of destination (either the final destination such as the buyer's facilities or a port of destination. This has to be agreed to by seller and buyer, however).

If the buyer requires the seller to obtain insurance, the Incoterm CIP should be considered instead.

CIP – Carriage and Insurance Paid to (named place of destination)

This term is broadly similar to the above CPT term, with the exception that the seller is required to obtain insurance for the goods while in transit. CIP requires the seller to insure the goods for 110% of the contract value under at least the minimum cover of the Institute Cargo Clauses of the Institute of London Underwriters (which would be Institute Cargo Clauses (C)), or any similar set of clauses. The policy should be in the same currency as the contract, and should allow the buyer, the seller, and anyone else with an insurable interest in the goods to be able to make a claim.

CIP can be used for all modes of transport, whereas the Incoterm CIF should only be used for non-containerized sea-freight.

DAT – Delivered At Terminal (named terminal at port or place of destination)

This Incoterm requires that the seller delivers the goods, unloaded, at the named terminal. The seller covers all the costs of transport (export fees, carriage, unloading from main carrier at destination port and destination port charges) and assumes all risk until arrival at the destination port or terminal.

The terminal can be a Port, Airport, or inland freight interchange, but must be a facility with the capability to receive the shipment. If the seller is not able to organize unloading, they should consider shipping under DAP terms instead.

All charges after unloading (for example, Import duty, taxes, customs and on-carriage) are to be borne by buyer. However, it is important to note that any delay or demurrage charges at the terminal will generally be for the seller's account.

DAP – Delivered At Place (named place of destination)

Incoterms 2010 defines DAP as 'Delivered at Place' – the seller delivers when the goods are placed at the disposal of the buyer on the arriving means of transport ready for unloading at the named place of destination. Under DAP terms, the risk passes from seller to buyer from the point of destination mentioned in the contract of delivery.

Once goods are ready for shipment, the necessary packing is carried out by the seller at his own cost, so that the goods reach their final destination safely. All necessary legal formalities in the exporting country are completed by the seller at his own cost and risk to clear the goods for export.

After arrival of the goods in the country of destination, the customs clearance in the importing country needs to be completed by the buyer, e.g. import permit, documents required by customs and etc., including all customs duties and taxes.

Under DAP terms, all carriage expenses with any terminal expenses are paid by seller up to the agreed destination point. The necessary unloading cost at final destination has to be borne by buyer under DAP terms.[13][14]

DDP – Delivered Duty Paid (named place of destination)

Seller is responsible for delivering the goods to the named place in the country of the buyer, and pays all costs in bringing the goods to the destination including import duties and taxes. The seller is not responsible for unloading. This term is often used in place of the non-Incoterm "Free In Store (FIS)". This term places the maximum obligations on the seller and minimum obligations on the buyer. No risk or responsibility is transferred to the buyer until delivery of the goods at the named place of destination.[15]

The most important consideration for DDP terms is that the seller is responsible for clearing the goods through customs in the buyer's country, including both paying the duties and taxes, and obtaining the necessary authorizations and registrations from the authorities in that country. Unless the rules and regulations in the buyer's country are very well understood, DDP terms can be a very big risk both in terms of delays and in unforeseen extra costs, and should be used with caution.

Rules for sea and inland waterway transport

To determine if a location qualifies for these four rules, please refer to 'United Nations Code for Trade and Transport Locations (UN/LOCODE)'.[16]

The four rules defined by Incoterms 2010 for international trade where transportation is entirely conducted by water are as per the below. It is important to note that these terms are generally not suitable for shipments in shipping containers; the point at which risk and responsibility for the goods passes is when the goods are loaded on board the ship, and if the goods are sealed into a shipping container it is impossible to verify the condition of the goods at this point.

Also of note is that the point at which risk passes under these terms has shifted from previous editions of Incoterms, where the risk passed at the ship's rail.

FAS – Free Alongside Ship (named port of shipment)

The seller delivers when the goods are placed alongside the buyer's vessel at the named port of shipment. This means that the buyer has to bear all costs and risks of loss of or damage to the goods from that moment. The FAS term requires the seller to clear the goods for export, which is a reversal from previous Incoterms versions that required the buyer to arrange for export clearance. However, if the parties wish the buyer to clear the goods for export, this should be made clear by adding explicit wording to this effect in the contract of sale. This term should be used only for non-containerized seafreight and inland waterway transport.

FOB – Free on Board (named port of shipment)

Main article: FOB (Shipping)

Under FOB terms the seller bears all costs and risks up to the point the goods are loaded on board the vessel. The seller's responsibility does not end at that point unless the goods are "appropriated to the contract" that is, they are "clearly set aside or otherwise identified as the contract goods".[17] Therefore, FOB contract requires a seller to deliver goods on board a vessel that is to be designated by the buyer in a manner customary at the particular port. In this case, the seller must also arrange for export clearance. On the other hand, the buyer pays cost of marine freight transportation, bill of lading fees, insurance, unloading and transportation cost from the arrival port to destination. Since Incoterms 1980 introduced the Incoterm FCA, FOB should only be used for non-containerized seafreight and inland waterway transport. However, FOB is commonly used incorrectly for all modes of transport despite the contractual risks that this can introduce. In some common law countries such as the United States of America, FOB is not only connected with the carriage of goods by sea but also used for inland carriage aboard any "vessel, car or other vehicle."[18]

CFR – Cost and Freight (named port of destination)

The seller pays for the carriage of the goods up to the named port of destination. Risk transfers to buyer when the goods have been loaded on board the ship in the country of Export. The Shipper is responsible for origin costs including export clearance and freight costs for carriage to named port. The shipper is not responsible for delivery to the final destination from the port (generally the buyer's facilities), or for buying insurance. If the buyer does require the seller to obtain insurance, the Incoterm CIF should be considered. CFR should only be used for non-containerized seafreight and inland waterway transport; for all other modes of transport it should be replaced with CPT.

CIF – Cost, Insurance & Freight (named port of destination)

This term is broadly similar to the above CFR term, with the exception that the seller is required to obtain insurance for the goods while in transit to the named port of destination. CIF requires the seller to insure the goods for 110% of their value under at least the minimum cover of the Institute Cargo Clauses of the Institute of London Underwriters (which would be Institute Cargo Clauses (C)), or any similar set of clauses. The policy should be in the same currency as the contract. The seller must also turn over documents necessary, to obtain the goods from the carrier or to assert claim against an insurer to the buyer. The documents include (as a minimum) the invoice, the insurance policy, and the bill of lading. These three documents represent the cost, insurance, and freight of CIF. The seller's obligation ends when the documents are handed over to the buyer. Then, the buyer has to pay at the agreed price. Another point to consider is that CIF should only be used for non-containerized seafreight; for all other modes of transport it should be replaced with CIP.